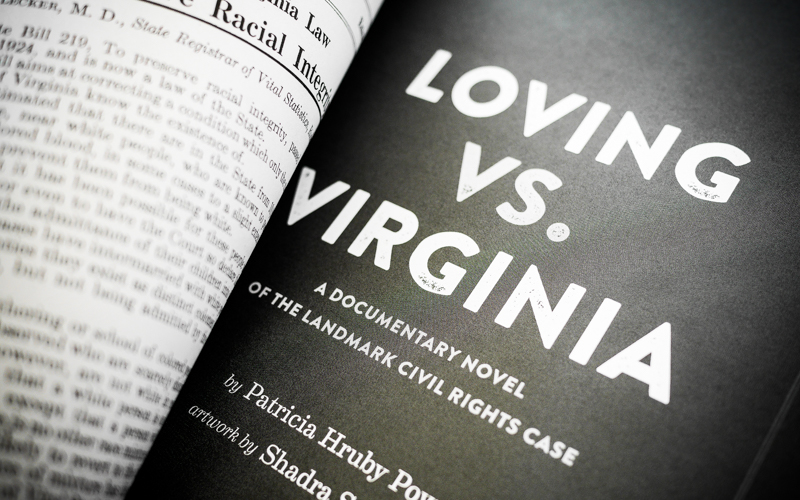

Close reading—the thoughtful, critical analysis of a text—is a valuable skill for today’s students, but it’s one that requires practice. Here, author Patricia Hruby Powell does a close reading of her new chapter-book-in-verse Loving vs. Virginia (based on the landmark civil rights case that legalized marriage between races). Students can follow along with the story and develop their own close reading skills by comparing Powell’s margin notes to her Loving vs. Virginia passages. We’re also giving away two copies of Loving vs. Virginia in honor or Loving Day on June 12. Enter here for your chance to win!

By Loving vs. Virginia author Patricia Hruby Powell

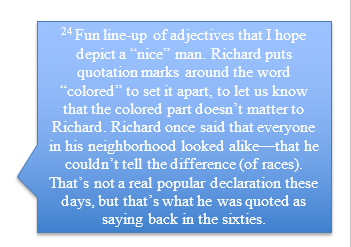

Let’s look at a couple of passages, take them apart and see how they were constructed.

First off, I “learned” the voices of Mildred and Richard, in order to create my version of their written “voices,” by watching Hope Ryden’s film footage of the young family taken in the early sixties. The footage can be seen in Nancy Buirski’s documentary “The Loving Story.” I hope that you find Mildred’s voice soft and lyrical. Richard’s voice is also soft, but with an edge of defensiveness. He doesn’t speak as smoothly or as grammatically as Mildred. Neither speaks with perfect grammar, but Mildred is closer to using standard grammar—in the way that I depict them, which is the way I understand them.

A Close Reading of Several Loving vs. Virginia Passages

Starting on page 90, Mildred is familiar with the segregation of the times in Virginia, but in this scene it becomes clear to Richard. It was the Lovings’ friend Ray Green who told me this anecdote. Some of the strongest scenes in my book Loving vs. Virginia I developed from the stories that Richard and Mildred’s friends and family told me about them.

Mildred – October 1956

This Saturday night,

Daddy and my brothers

are the band

for a square dance

at Sparta School—

the elementary school

where Richard went—1

the white school.

Colored people

aren’t allowed in.2

Even though the band is

colored—

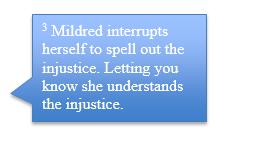

and that’s my family

in there—3

I can’t go in.4

I know that.

Light and music

spill out the open door

We’re milling around

with a big group of coloreds

outside

where we’re allowed

to listen

and dance

if we want.5

Richard and his

car buddies,

Ray and Percy—

and Ray’s girl,

Annamae—

are with us.

Ray, Annamae, and Percy,

being colored,6

aren’t allowed in,7 either.

White guys

with white girls on their arms

say

“Hey” to Richard

on their way in.

He “heys” them back.8

Everyone likes Richard.9

He says to me,

“Let’s go in.

They won’t mind.”

“We can’t go in there.10

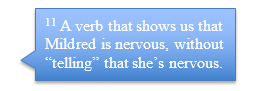

I giggle 11

cause I think he’s kidding.

But he’s got his arm

around my shoulder

walking toward the door

and he’s a whole lot stronger

than me.

As we step into the doorway

a white man,

maybe the guard,

puts out his hand—

bars our path.

He looks at Richard

and cocks12 his head at me—

like

that says it all.

I know I’m not allowed,13

and I know that’s not right,

but what I feel

is—embarrassed.

Humiliated.

I don’t care if I go in.

I don’t like to rock the boat.14

“You go in, Richard,”

I say, my voice rising.

“You wanna dance?

You go in.

You wanna listen to the music?

You go ahead.” 15

I feel my lower lip jutting out.

That’s how I know

I’m angry.

I train myself not to be angry.

So I don’t always know that I am.16

Anger takes energy

that I’d rather use

being happy.

But now I’m angry—

and I’m angry

at Richard.

I don’t want to cry,

but I feel my lower lip

trembling—

my face17 is warning me

that the tears could start

spilling.

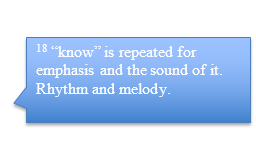

Richard knows me well

enough

to know18 this too.

He pulls me back

out of that lit up

doorway,

out to where it’s dark

away from the people.

He puts his

arms around me

and he kisses my eyes

which are salty with

escaped tears.19

He says,

“Bean,

“Bean, I’m sorry,

but your Daddy is playing in there

and Doochy and Button,

and all of ‘em, Theo,

and I thought maybe

they’d let us in.20

It was stupid.

I was stupid.

Let’s hang out here.

It’s nicer out here,

in the dark,

anyhow.”

And Richard,

who never ever

dances,

just holds me

and we rock together

taking little steps

and we’re

dancing.

The moment they said,

No, you can’t go in,

he saw—

I know he really saw—

what it is

to be colored.21

Starting on page 31, Richard, who is white, has just been walking down the road when his black friend Ray Green picks him up in his car. Sheriff Brooks has stopped them because he doesn’t like seeing whites and blacks together in a car.

Richard – Fall 1952

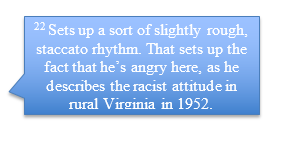

Me, I’m white, but my daddy,22

he drives a truck for P.E. Boyd Byrd—23

maybe the richest roundest jolliest “colored”24 farmer in the section.

In other parts, a white man working for a colored man—

that would be unusual.

But that’s how it is here in Central Point.

Sheriff don’t like this one lousy bit.25

White man puts hisself beneath a colored man?

Workin’ for him?

Worse than being colored, right, Sheriff?

Course, I didn’t say that.

Just thinkin’.

Sherriff looked like26 he was chewin’ on his teeth,27

kept turnin’ over that itty bitty license,

trying to figure out what mean thing he could do to us.

We wait quiet

while he walked back to his car.

To Sheriff Brooks there are only two races—

white and colored.

In all of Virginia, just two races—

white and colored.28

We know Sheriff ain’t done with us,

but he let us go for now.

Starting on page 226, Mildred has just heard that they’ve lost the fourth hearing of their long case, which means we’re leading up to the final hearing of the U.S. Supreme Court. She’s in the country, which she loves, reflecting on their lives.

Mildred – March 1966

A group of big black crows

stands around on the stubbly29 land—

until the children run at them.

The crows take off,

float30 on the wind.

Some try to make their way

into the wind but the wind

won’t allow it.31

The crows seem to say,

I want to go over there

but the wind says, no, I want you here.

So they let the wind carry them

real graceful on outstretched wings.

I think,

that’s like our life.32

We’re those crows.33

The wind is casting us around—34

go live here,

now you can live there,

now get on over there.

You can’t control the wind.35

They say we’re making progress.36

I hope some of this information will help you with your own writing.

—Patricia Hruby Powell

Leave A Comment