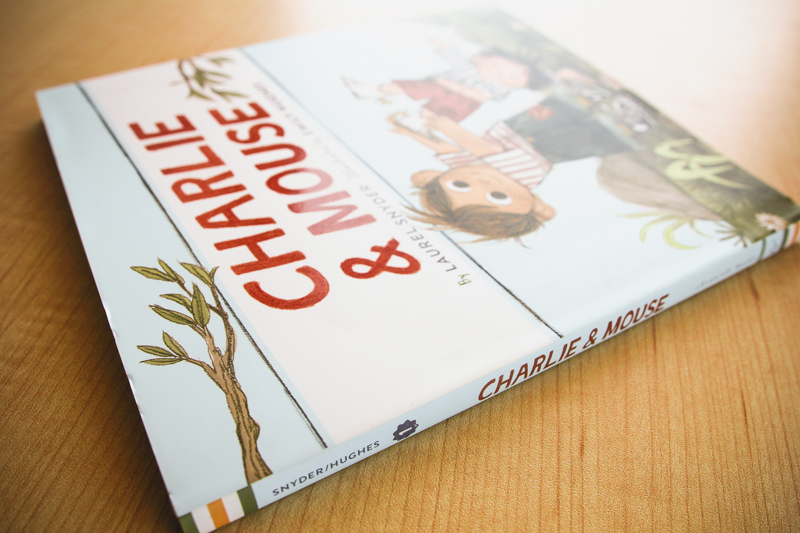

This may sound funny, but Charlie and Mouse actually grew out of Facebook. After my kids were born, I began chronicling each sweet or goofy thing they said or did. My intended audience was (of course) my kids’ grandparents, aunts, and uncles. But after awhile, other people started to comment that these moments were interesting, and might actually make a good book.

While I couldn’t see at first how that might be, I did take the advice seriously enough to shift over from Facebook to a journal. There I wrote often, chronicling the tiny details I noticed each day, the things that might otherwise have faded from my memory. Like the time my sons asked me for a bedtime banana!

Sometimes they were cute things, and something they were annoying things. I just wrote what I saw. I never tried to tell a story, really. I just kept using the Facebook post format—a few simple lines at a time. A funny quote from a kid, or a description of something I saw them do. Say, trying to catch a fish in an ice bucket, or trying to sell rocks

Then a few years later, I was taking a walk with a friend in my Atlanta neighborhood, and she suggested that I might want to write about the place where I live, about the people in it. Suddenly, I knew what to do with the journal!

A place is not a story, and a moment is not a story. But a handful of moments in a place? That might just be a story!

In this organic way, Charlie and Mouse were born, along with their home, their family, and the friendly neighborhood around them. Had I set out to write a memoir, I never would have thought to do it in this way, but by chronicling the little moments, the discreet memories, I think I captured something I might otherwise have missed.

As a format for learning to tell a story, I think this makes a great model for kids. A young storyteller can easily feel daunted by the basic mechanics of writing, as well as the task describing an entire world and establishing a narrative within it. But most kids can think of a sentence a day. One funny or goofy or sad or sweet thing they saw or heard or did. What’s more, they enjoy it! And when they look back, weeks later, and see how the moments often add up to something more, it’s illuminating.

When we remove the pressure to chronicle “What Happened Today” or “What I Did Over Summer Vacation” we free kids up to tell us what they actually experience, in a more momentary way.

Which is almost always fascinating.

So How Can You Use This Model in the Classroom?

1. To begin with, have students keep a journal of moments. Each day (or week), ask them to share (in writing or verbally, depending on age/skill) something distinct. When I do this myself in school visits, as part of a writing workshop, I try to impress upon the kids that I want to hear the details that NOBODY ELSE will think to mention. Every kid has things that are theirs alone, moments nobody else notices. Spots in the yard or house that they visit alone, ways of eating, or favorite words. When authors write, they are attempting to tell the story that only they can tell. Kids can do this too!

1. To begin with, have students keep a journal of moments. Each day (or week), ask them to share (in writing or verbally, depending on age/skill) something distinct. When I do this myself in school visits, as part of a writing workshop, I try to impress upon the kids that I want to hear the details that NOBODY ELSE will think to mention. Every kid has things that are theirs alone, moments nobody else notices. Spots in the yard or house that they visit alone, ways of eating, or favorite words. When authors write, they are attempting to tell the story that only they can tell. Kids can do this too!

2. Consider having them build these moments out. They can be used (especially with older students) as the seed for a story. Ask them to choose a moment from their journal that’s especially fun, and then tell you what happened before and after the moment. Or ask them to convert the moment into a bit of dialogue. To develop the single sentence into three or five or ten sentences, as is appropriate to skill. Is there a way this moment, when extended, might teach a lesson, or turn into a joke?

3. Students sometimes enjoy adding magic! Ask them to select a moment from their journal and then add a magical element. To grant the “character” in their story the power of flight, or to introduce a dragon. This is a chance to discuss fiction and nonfiction, and how a true story can be the root of a fictional story. All authors do this!

4. Have students collaborate. As I did in Charlie & Mouse, pull the moments together within a unifying space. These might be “the Adventures of Mrs. Weatherford’s Kindergarten” or “A Day in Room 109.” You might even want to “publish” the collection for parents.

5. An alternate way of collaborating might be to have the students share their moments aloud. You can do this using an “and then” connector, so that you (as the initial storyteller) introduce a character, and then have students build onto the story by offering their moments.

Many thanks to author Laurel Snyder for sharing her writing process with us. What great inspiration for using her early chapter book as a mentor text for writing! And don’t forget to look for Charlie & Mouse & Grumpy, the sequel to Charlie & Mouse, when it publishes in October 2017!

Leave A Comment