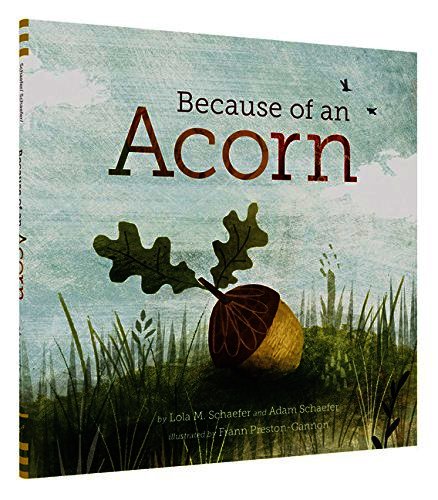

By Lola M. Schaefer, author of Because of an Acorn (Chronicle Books, 2016)

Changing Earth. The Golden Geography: A Child’s Introduction to the World; Simon and Schuster: New York, 1952.

I still remember the first book that excited me about science. I was eight years old and the title was Insects. It wasn’t a field guide, but an illustrated children’s book all about the bugs in my backyard: katydids, ladybugs, moths, beetles, butterflies and praying mantises. That was more than fifty years ago and yet this summer when I saw several walking sticks around our home, I smiled. Why? Because I could still see that particular half-page illustration and description in my memory.

Never as a child did I imagine that one day I would be an author of children’s books. But I am. And not only that, many of my are published titles are about the natural world. I can truthfully say that the few illustrated books I owned as a child about earthquakes and volcanoes, the planets, and animals, ignited a curiosity in me that has only grown over time.

Bringing Science to Readers through Books

Whenever I write about the sciences, I have two goals. First, I want my book to be a lure, appealing and intriguing, so the reader becomes engaged in every way possible. Next, I hope the reader enjoys the information and sets out to learn even more about the topic through firsthand experience or another book.

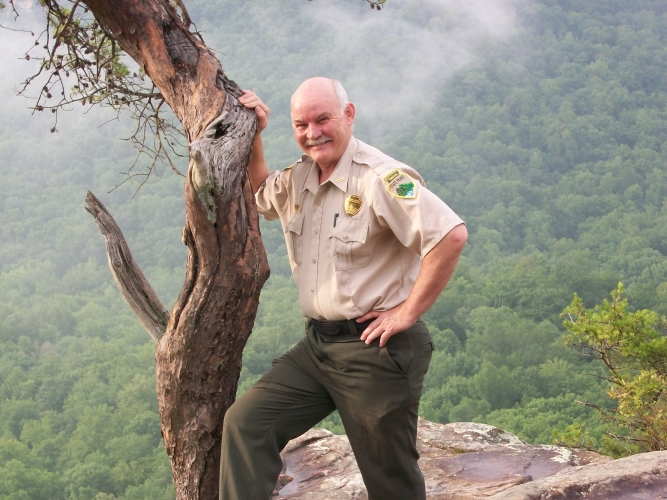

State Naturalist Randy Hedgepath

Even though many of my nonfiction books have little text, the research behind each word is phenomenal. When I write about the sciences, I am promising the reader that the facts are accurate. Rather than get my information from the internet or published books, I speak with experts who are currently working in a field of study directly connected to the topic. For me, that’s one of the most rewarding parts of the process. I am able to learn the latest and most reliable findings that exist to date.

Because of an Acorn (Grades P-K, Level E, Lexile BR), which I researched and wrote with our older son Adam, is about the complex interdependence of plant and animal species in a white oak forest. I took a two-day field trip to a Tennessee State Park which is on the Cumberland Plateau. There I worked with one of the state park rangers to learn all about the different plant and animal species that are dependent on the acorn. I took notes as we hiked the trails leading to the forest.

After I returned home and Adam and I began to write, of course, we had more questions. When you find a knowledgeable and helpful resource like we had in Randy Hedgepath, it makes the writing so much more enjoyable. But once all the information is available, it’s time to find a structure that will engage the reader, compliment the information, and, hopefully, be an art form of its own. No easy task.

For this book, we knew the structure needed to show the reliance of plant and animal life on the foundation species of the white oak. After a few misses, we focused on cause and effect that begins with the acorn and continues through the seasons until the final spread shows a thriving forest.

Because of an acorn,

a tree.

Because of a tree,

a bird.

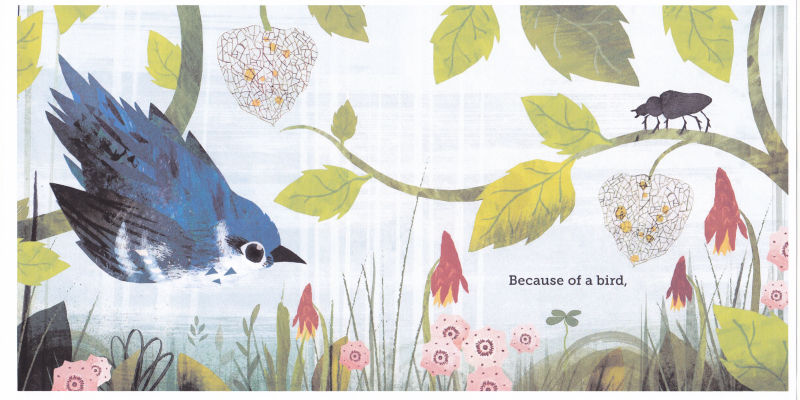

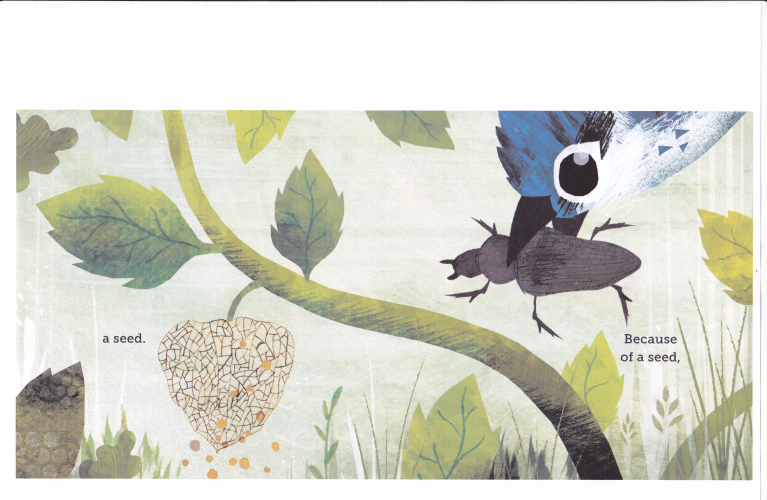

Because of a bird,

a seed.

The language shows how one element of the forest depends on another. Frann Preston-Gannon added another layer of meaning with her illustrations. The art not only shows the cause and effect mentioned in the text, but other plant and animal life in this forest ecosystem. Young readers quickly notice how important a role the acorn plays in this web of life.

Helping Students Make Connections

Helping Students Make Connections

I’ve already had the pleasure of sharing this book with teachers and students. Teachers are excited to find a book that shows the relationships between different members in one ecosystem. As we know, science is much more than definitions and memorization. It’s learning how one living organism impacts another. It’s about systems, relationships and . . . cause and effect.

Primary students enjoy the book because they can hear in the words and see in the illustrations the connections between each plant and animal. In fact, they enjoy studying the pictures and noticing all that’s going on so they can predict what’s going to happen on the next page. The sparse text leaves room for high engagement on many levels.

As an author, my heart soars to listen to the students’ connections.

“I have acorns at my house. Do you think they will grow trees?”

“We had a hawk that carried away a snake.”

“I thought that the snake was going to get the chipmunk. I’m glad the hawk got it first.”

“I knew birds ate seeds, but now I know they eat insects, too.”

I can tell from the comments that because of this book, readers will look at their backyards, their parks and their national forests with the eyes and heart of a scientist.

Because of a book,

a scientist.

Leave A Comment