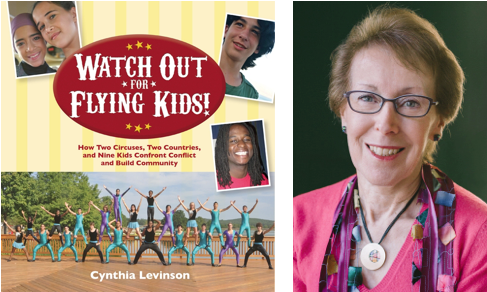

It’s not every day that I come across a book that truly expands my world. Watch Out for Flying Kids (Grades 5-9) did just that, and I am grateful. You see, part of this poignant story takes place in my own hometown, St. Louis, Missouri, and was published at a time when I needed this story most. I met Cynthia Levinson (one of those incredibly positive forces in our world) this past summer in St. Louis at the International Literacy Association conference. She told me a little about the book and its St. Louis connection, which prompted me to read it.

Watch Out for Flying Kids profiles nine young people who participate in youth circus programs. One of the circus groups resides in St. Louis, the other, in Israel. What’s unique about these circuses is that they are made up of students who do not normally interact. Circus Harmony, in St. Louis, is made up of kids from the inner city and suburbs, and Circus Galilee, in Israel, includes Jewish and Arab kids. The two circuses become intertwined when the troupes begin a cultural exchange, traveling from one country to another to perform together. This may not seem remarkable at first, but imagine it: two groups of kids from completely different backgrounds (sometimes from conflicting groups) who speak different languages, coming together to create and perform a full-on circus! It’s awesome!

The stories of the nine left me in a state of wonder. Not only did these young people perform incredible, physical feats, but they also seemed mostly unaffected by their differences. The circus had the power to overthrow the social stigmas around them and let them focus on something more important—coming together to accomplish something fun and meaningful. This book was published not long after the events in Ferguson, Missouri, a suburb of St. Louis, sparked violent protests amidst cries for justice. At a time when I feel sad and at times helpless about the state of race relations in my city, this amazing story gives me hope that things will change. We need more books like this one.

Read more about this amazing story in an interview with author Cynthia Levinson:

Q: What was your inspiration for Watch Out for Flying Kids?

A: Unlike my first book, the inspiration for Watch Out for Flying Kids was not a flash of recognition that “this is a story I must tell.” It was more layered and sequential. In fact, the first book, We’ve Got a Job (Grades 5-12. Level Y, Lexile 1020), provided a stimulus for this one.

Taking a break from researching the black kids who changed Birmingham in 1963, I joined my husband on a trip to Israel and decided to look into Jewish and Arab kids who were changing their world. Initially, I thought I’d focus on a Hebrew-Arabic bilingual school but, after two days of research, I realized that I’d have to move to Israel for several months to do it justice. When I learned about a Jewish-Arab youth circus, I thought, “Circus? Cool!” and went up to the Galilee to visit it.

However, I had no idea if there was a story. Unlike Birmingham during the civil rights period, which is very well documented, the circus was unfolding in real time. There were no secondary sources whatsoever; nothing had been written about social circus; and I had no idea where, if anywhere, it was going. The primary sources were in front of me—kids doing forward rolls and falling off of stilts in a gym while chatting with each other in two languages I don’t understand. Most of the Galilee is so thoroughly segregated that merely the fact that these kids were in the same room together was a rarity that intrigued me. But it wasn’t a story.

I flailed for a couple of years, visiting other youth circuses in the U.S., including Circus Harmony, the Galilee Circus’s partner in St. Louis. But I was still not sure which troupes to follow. The incident that finally propelled me to write the book was a comment that fourteen-year-old Hla Asadi made. Hla is an observant Muslim teenager who is also a contortionist. She is always fully covered from the hijab on her head to her ankles. I asked her if people in her village, which is entirely Arab, were upset that she participated in a program with Jews. My innocence exasperated her.

She said, “Nobody could understand. Even you. Could you understand that Arab and Jewish people could be together?”

Except for her immediate family and the other kids in the circus, no one in her world could even conceive of the possibility of Jews and Arabs playing together. It was literally unimaginable. Yet, there they were, literally supporting and catching each other. Watching kids accomplish the inconceivable convinced me that I had to find and tell their story.

Q: Can you tell us about your research process?

A: The research was a combination of exhilarating, onerous, and hilarious. Exhilarating because I got to spend hundreds of hours behind the scenes at circuses, seeing how kids learn to plant their feet next to their ears while lying on their stomachs; walk en pointe in toe shoes along a tight wire; juggle clubs behind their backs; unfurl down lengths of fabric from the ceiling and catch themselves an instant before hitting the ground.

Also, I spent nine days living with Jewish and Arab families—the Shafrans and the Asadis—in the Galilee. If you’ve heard of Middle-Eastern hospitality, you’ll know what this means. The number of dishes at every meal! The multiple ways of cooking eggplant! The warm pita and fresh hummus! In addition, circus people all over the world pride themselves on welcoming everyone as family. So, in St. Louis, I moved in with the Hentoffs, who made me feel at home. All of these experiences were invaluable for immersing myself in the Middle East, the Midwest, and the universe of circus.

The research was also onerous, however, because only four of the nine kids featured in the book live in the United States. One of the Americans was in professional circus school in Canada, and the Israelis, of course, were in Israel. So, I was dealing with three time zones and two foreign languages.

Technology glitches also intervened. When I couldn’t talk with the kids face-to-face, we communicated by whichever means worked best for them—telephone, email, text, Skype or Facebook messaging and video—as long as the devices, the cell towers, and the internet connections worked. When one of those went down, so did the conversation.

Then, there was the fact, as I mentioned, that they and their coaches—who spoke, variously, Hebrew, Arabic, German, Mongolian or occasionally English—were practically my only sources of information. Unlike many nonfiction books, Flying Kids is not based on archival research; there are no archives. Instead, it was a journalistic effort. The investigations that did not involve personal interviews and observations consisted of prowling the kids’ and the circuses’ Facebook pages and email exchanges and beseeching them for photos and videos. I did read some secondary works, which focused on the practice and history of circus, the history of the Middle East, and the growth of St. Louis.

Frankly, the hardest factor of all was that the “main characters” were all teenagers with much better things to do than talk with me about their childhoods. I kept a log of the times that various ones of them “stood me up” (in my definition). Not infrequently, what I thought was an appointment for an interview, complete with a hired translator, turned out to conflict with homework. Or rescinded cell-phone privileges. Or a mood swing. Or with an urgent need to go to the beach—the photos of which I could simultaneously and maddeningly track on Facebook! I could hardly blame them. But I could and did gnash my teeth. I began to call this “the book I cannot write.” I sent so many messages to my editor explaining why I could not write it that she sent me a copy of The Little Engine That Could!

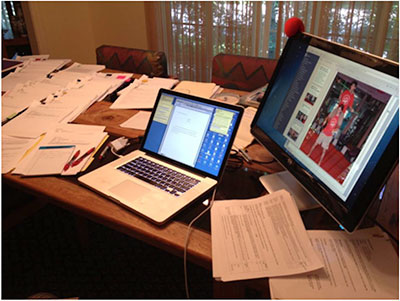

Searching out and acquiring all of this information was only the beginning. After transcribing over 120 hours of recorded interviews, I sub-divided them by topic, which I sorted into a searchable database. I also constructed a very detailed Timeline. Then, I printed everything out and spread it in piles across my dining room table, where my clown nose, The Little Engine That Could, and I sat for three months while I crafted the stories.

The hilarious part happened when I was trying to figure out what kids age 10-14 know about the Galilee. I asked writer friends, and one reported,

“I asked my neighbor’s daughter, who is 13. Said she, ‘Isn’t that where Puff the Magic Dragon lived?’

Me: ‘I’m fairly certain he frolicked in Hana Lee.’

Her: ‘Well, I know it has to be a place. I just don’t know where. Probably far, far away, like Florida.'”

Q: Did one of the stories of the nine kids you profiled particularly resonate with you?

A: Surely, Iking’s story has to be the most stirring. Raised with seven siblings by their grandmother in a two-bedroom house, he had the most trying upbringing. In and out of gangs, school, circus, and even once jail, his prospects were the most precarious. Yet, he has a huge smile, a winning personality, common sense, and determination. Jessica Hentoff, the head of Circus Harmony, helped raise him as did his mentor, Diane Rankin, though both were not infrequently frustrated with him. Today, he’s an internationally successful circus performer. And he’s engaged to be married! To see him talk about his story, check out the video below:

Iking

Q: Throughout the story, you describe so many amazing feats performed by young people. What was the most remarkable for you?

A: You’re right—the kids are phenomenal performers! I gave some examples above of their amazing prowess. It’s hard to believe until you see them in action, which readers can do on my website, and on Circus Harmony’s, and the Galilee Circus’ websites.

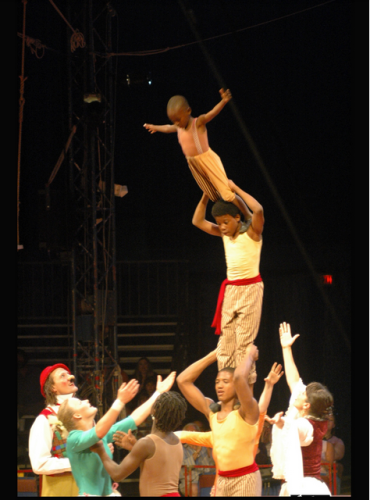

Rather than particular tricks, though, I think there are two categories of feats that impressed me most. One is watching kids repeat a trick that they get wrong, even in performance before an audience, to get it right. One of the videos I show in my presentations includes footage of Chauncey in a professional show. He’s standing on Kellin’s shoulders, and he tries to do a backflip and land standing on Max’s shoulders. He misses the first time and falls. So the three guys try again—and Chauncey nails it! The crowd whooped, for good reason. The ability not to be embarrassed, to realize that success entails failures, to concentrate in front of the public, to know that you can rely on your teammates—all of that is tremendously inspiring.

The other accomplishment that impressed me involved the Israelis, especially Roey, who learned to share the joy of circus with the audience. He was emotionally scarred during the Second Lebanon War when he was eight and became deeply fearful and self-conscious. Through circus, he gained not just confidence but also showmanship so that he and his partner could be spontaneous, crack jokes, involve the audience, and uplift others. That’s what circus is all about.

Q: During all of your interactions with Circus Harmony and Circus Galilee, did you ever dream of being a circus performer? If so, what would be your act?

A: After I finished writing the book, I remembered that my parents took me to the circus when I was about ten, and I came home with both a glossy brochure and a craving to live on the Ringling train. Since I had absolutely no athletic ability, the only way I could imagine getting a berth was to perch on an elephant. Ta da! Until three years ago, that was the beginning and end of my circus fantasy.

However, as part of my research—this is the hilarious part—I tried tight wire, trapeze, lyra, globe-walking, juggling, silks, and mini-trampoline. A failure at all of them, I’m content to applaud the kids who can actually do those things.

In the end, my circus dream isn’t so much about the acts in the show as the values behind the scenes—mutual support, lack of competition, risk-taking in a safe environment, and persistence. My act is conveying those in the book.

Q: Your website says that you write nonfiction for and about young people. What about this audience and time of life interests you?

A: I think there must be a twelve-year-old living in my head. That’s the voice I hear. I like the challenge of making complex subjects appealing to middle-graders—taking them seriously while engaging their imaginations. Revealing urban America and the Middle East through circus is the perfect example.

Q: What did you learn about the world and/or yourself through circus?

A: Everyone really can accomplish the seemingly impossible, in some way.

This includes kids who do unbelievable things with their bodies and overcome impassable social and political barriers. It also includes writers, such as me, who plow through immovable obstacles, both internal and external, to produce the book they couldn’t write.

Q: What advice do you have for students assigned to write informational reports?

A: Imagine. Interact. Engage.

This is probably uncommon advice for report-writing; often, teachers emphasize research. But here’s why I recommend these.

Imagine yourself in the situation, the place, and the time that you’re writing about.

Interact with the people (or maybe the animals or nature or space, depending on the topic) around you.

Engage your reader with the details, actions, and feelings you observed that make the information come alive.

The only way to do these successfully is to do solid research. But it becomes research with a purpose—taking your reader where you’ve been—rather than just a recitation of facts.

Q: How do you envision Watch Out for Flying Kids being used in the classroom?

A: There are so many ways for kids to imagine, interact, and engage in the classroom with Watch Out for Flying Kids! The book encompasses three stories in one.

There’s the urban America strand in which the major themes are race and social class.

There’s the multi-cultural strand in which the themes include politics and religion in the Middle East.

And there’s circus! How fun is that?

Also, layered throughout, there are issues related to resolving conflicts, taking risks, perseverance, and the role of children in causing social change. Furthermore, with feet on two continents, it’s hard to find a nonfiction book as diverse as Flying Kids. With all of these threads, it connects with the Common Core, social-emotional learning, and cross-curricular programs since it’s relevant to social studies, language arts, theater, even PE.

Peachtree has developed a wonderful teachers’ guide, which will be available shortly on their website and mine. It incorporates a lot of skills and correlated readings. A few of the activities include:

Discuss the similarities between two kids who come from very different backgrounds. One of the points of the book—and of circus—is focusing on what we have in common, not what separates us.

Try something new. It doesn’t need to—and shouldn’t!—be as challenging as tumbling. But whirling a hula hoop around your wrist, singing a solo in front of the class, sitting at a different lunch table are all examples of taking risks, like the circus kids.

Look at the mathematical connections to juggling. Scientific American has a great website for this.

Find circus-related words—such as juggle, trouper, tight rope—that are used as metaphors in everyday language to see how circus pervades our lives.

Make a plan to draw diverse groups of kids at school together.

Q: Anything else that you want to tell us about? Your next book perhaps?

A: Thanks for asking! My next book, coming out on January 5, 2016, is a biography for eight- to twelve-year-olds titled Hillary Rodham Clinton: Do All the Good You Can. Because I knew Hillary in college, many of her friends and former staffers were willing to talk with me and share kid-friendly stories. So the book not only covers her life and many accomplishments but is also accessible and entertaining for readers. Kirkus Reviews calls it “a respectful, insightful, and inspiring portrait.”

Thank you, Emma, for this opportunity to talk about Watch Out for Flying Kids!

Leave A Comment