Photo Courtesy of Anna N. Zytkow

Your graphic novels are unique in that they all focus on the history of different topics in science. What is it about this subject matter that lends itself so well to graphic novels?

This is a question I’m asked often, and it’s one I like because I get to suggest an experiment. Go to your local bookstore or library and browse the literature shelves. Flip through a bunch of books; you don’t have to read them if you don’t want. In fact, please don’t. Just take a quick glance at what’s inside. Then head over to the science section and do the same thing. Now…where did you see the pictures? You probably don’t even need to do this in real life to know the answer. (If you simply imagined yourself doing this, you performed what scientists call a Gedankenexperiment, by the way; it’s German for “thought experiment.” There’s your science vocabulary word for the day! Ahem. Sorry.) Scientists communicate with words and images (always have, always will). So what could be more natural than using comics to tell stories of science?

When did you become interested in the comic book format and what led you to begin writing graphic novels?

I became interested in comics at an early age, starting with the daily strips I’d read in the newspaper. In college in the 1980s, I discovered the new-at-the-time “graphic novel” form. I do comics about scientists in part because of Steve Lieber, a noted comic-book artist and a good friend of mine. I had loaned him a copy of Richard Rhodes’s book The Making of the Atomic Bomb, and he pointed out that a wartime meeting between Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg, which Rhodes described briefly, had great dramatic potential. When Steve and I talk about dramatic potential, we usually mean in comics. So I asked him if he’d draw the story if I wrote it up as a comics script. Knowing I’d never done anything like that at the time, he no doubt felt it was safe to say yes. A year or so later, I was sitting on the floor of his apartment, helping clean up the art (erasing stray pencil lines and filling in blacks) prior to taking my first book, Two-Fisted Science, to the printer. Interestingly enough, a year later Michael Frayn’s superb play, “Copenhagen,” came out, and it also revolves around the Bohr-Heisenberg wartime meeting.

In general, who is the intended audience for your graphic novels?

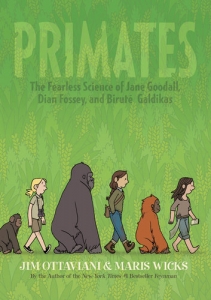

The age range, or the sweet spot, I have in my head varies from book to book, but my intended audience is always the same: the curious. For example, Primates was intended for early teens, but got reviewed in Nature, one of the most respected and capital-S serious scientific journals in the world, read mostly by professorial types. So you never know, and that of course makes me happy!

Why is the graphic novel format important in literature?

I’m tempted to ask you to define “important” and “literature” before I answer the question, but I’ll restrain myself. (Sort of.) Seriously, I don’t really know if it’s important in literature, but I do know that through graphic novels I’ve been able to reach an audience that would very likely never pick up a biography of a scientist if it was told only in words. I think the format has an inherent appeal to many readers, and we want more readers, right?

Okay then, why do you think young people should read graphic novels?

Well, I’m not going to advocate for graphic novels instead of novels without pictures, or nonfiction, or blogs or Twitter or…you name it. I think young people and old people should read a lot, and in as many genres and formats as possible. I hark back to the saying, often attributed to Mark Twain, which I’ll paraphrase as “A person who doesn’t read has no advantage over someone who can’t read.” So: read.

Your most recent book, Primates, came out last June. Where did you get the idea for this book? And, what kind of research did you do?

I had already written about Biruté Galdikas before, in my second book (Dignifying Science), and I knew the general outline of Dian Fossey’s life story. Oddly enough, I knew the least about Jane Goodall, probably because she’s a household name and I had her safely tucked away in the Famous People Everybody Knows Of category in my head. So what I wanted to do was get to a point where I could move her into the Famous Person I Know Something About category. Again, if I’m curious about something, a great way to learn more about it is to do a book about it.

she’s a household name and I had her safely tucked away in the Famous People Everybody Knows Of category in my head. So what I wanted to do was get to a point where I could move her into the Famous Person I Know Something About category. Again, if I’m curious about something, a great way to learn more about it is to do a book about it.

As for the research, I did a lot of reading. If you look through the bibliography of Primates you’ll see that collections of letters written by Dr. Goodall figure prominently, as do books written by Drs. Fossey and Galdikas, especially books containing excerpts from their diaries and journals. We’re lucky that all three scientists started their work in a time where letter-writing and journal entries were the way people recorded their daily lives. I think in many ways it will be harder for researchers to get first-person accounts of what happened on a day-to-day basis now that we record our thoughts via tweets and Facebook updates and emails. Anyway, I combined those first-person accounts with articles from all sorts of magazines and books about primates, and Louis Leakey as well, to build out a picture of their groundbreaking research and the lives they led while doing that work.

With graphic novels, the relationship between the text and pictures is more important than ever. Can you tell us what is like working with an illustrator in this particular format?

I always write a detailed script (“Page 1, panel 1: Jim is sitting at his desk in Michigan, answering questions for Booksource. He’s dressed for success, in a road race t-shirt, sweatpants and no shoes.” Etc.) so the story elements are all there—I hope!—when I hand the reins over to the artist.

That said, once Maris began drawing Primates the story was no longer mine; it became ours. So she moved things around, restaged certain scenes, and did all the heavy lifting that it takes to bring words into life as pictures. We of course talked things over as she went along. Sometimes what I wrote didn’t work on the page the way I hoped it would. Sometimes she had a better idea for how to get a story point across. So we would talk between ourselves and with Calista, our editor. It’s an iterative process, trying to find that exact right moment, and expression, to depict. And if in the end what readers see isn’t what I originally intended, nobody will ever know (often times not even me, since I try not to look at my script as the art comes in; I only going back to read what I wrote if something doesn’t ring true as drawn). If the drawing works, it’s the right drawing…even if it’s not the drawing I originally imagined!

Who are your favorite graphic novel authors? Do you have any favorites that you would recommend for younger readers?

There are too many authors to name, so please know that I’m skipping lightly across the surface when I mention—off the top of my head, but alphabetized!—Neil Gaiman, Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, Roger Langridge, Linda Medley, Alan Moore, Harvey Pekar, Raina Telgemeier, Jeff Smith, Brian Vaughn, Chris Ware, and Gene Yang. I could easily double or triple the length of this list if I walked over to my bookshelves and got methodical about answering the question.

As for younger readers, I’ll pull out Gilbert Hernandez (Marble Season), Roger Langridge (Snarked, and his Muppets books), Linda Medley (Castle Waiting), Raina Telgemeier (Smile and Drama), Jeff Smith (Bone), and Gene Yang (American Born Chinese, Prime Baby and Boxers & Saints) for starters, then add in books by Vera Brosgol, Ben Hatke, Hope Larson, Dave Roman…and again, there are many more that escape me right now or that I don’t even know about!

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Leave A Comment